How Culture Can Sometimes Be Distilled into a Single Word

Else Gellinek

- November 13, 2014

- 14 min read

- Language

This post is my contribution to the Day of Multilingual Blogging 2014. Readers will find the following languages: English, German, Italian, French, Romanian, Spanish, Polish, Russian and Greek. The main body of the post is written in English so that those who took the time to share their thoughts with me will be able to understand how I used their words.

Ein paar einleitende Worte

Zum Anlass des Day of Multilingual Blogging 2014 habe ich mich mit den tieferen Bedeutungsebenen sprachlicher Ausdrücke beschäftigt. Die feinen semantischen Aspekte eines Wortes oder eines Ausdruckes offenbaren sich häufig in der Übersetzung, wenn vergeblich nach einem passenden Gegenstück in der anderen Sprache gesucht wird. Sprache ist formgewordene Kultur und so werden Sprachen niemals über identische sprachliche Formen verfügen. Wir Übersetzer blicken täglich von dieser Metaebene auf unsere Sprachen. Deswegen wissen wir um die besondere übersetzerische Herausforderung, vor die uns bestimmte Begriffe in der Sprache stellen. Diese sogenannten unübersetzbaren Wörter verweisen auf Konzepte, die in anderen Sprachen entweder nicht lexikalisiert sind oder nicht bekannt sind. Hier offenbaren sich die kulturellen Unterschiede, die das Erlernen einer Fremdsprache so lohnenswert machen.

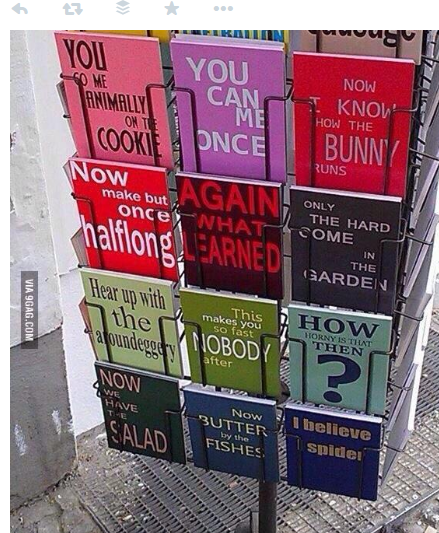

Words + grammar ≠ language

Everyone who has ever learned a foreign language is familiar with that feeling of being faced with the features of a language that have no counterpart in your mother tongue. There are unfamiliar sounds, unfamiliar grammar rules, and then there are phrase-level idiosyncrasies: the infamous idioms. Knowing which expressions are idioms and cannot be translated literally is vital. We have all met foreign language learners who fall into the trap of transporting idioms from their native language to the foreign one. For instance, Dutch soccer coach Louis van Gaal has a fateful tendency for forcing Dutch idioms into English. Apparently, he is so known for this that it gave rise to a Twitter parody account.

A glimpse of what lies behind language

People who don’t work with language professionally will not often pause to analyze their every-day speech like language professionals do. We know that sometimes a single word can convey so many subtle layers of meaning that it cannot be translated without losing some of that meaning.

For this year’s post for the Day of Multilingual Blogging, I asked various translators who work with English to share some culturally specific expressions in their native languages that are difficult to translate into English and require additional explanations to be understood in their entire breadth of meaning (if at all possible). As Alina Cincan said in an email (which I am shamelessly quoting): “It’s actually fascinating to see all these words with no exact equivalent, but sharing so many similarities yet being different at the same time.” I agree!

So, let’s get started. Explanations for the German expressions are mine. After each explanation, you’ll find the name of the contributor in brackets. At the end of the post, you will also find a complete list of contributors.

Heimat ist kein Ort, Heimat ist ein Gefühl! (Herbert Grönemeyer)

The German concept of “Heimat” is difficult to translate. It refers to your home country, but also to a feeling of belonging. It is a yearning for former times, as evidenced in the film genre “Heimatfilme,” which depicts a safe world, usually in small traditional German villages somewhere in the Bavarian mountains. There, the traditionally dressed community is rocked by some kind of crisis, but manages to resolve it and uphold traditional values. They then enjoy a happy ending, often involving cheesy, pink sunsets. These films were especially popular in the aftermath of WWII.

Other cultures have their own history and thus their own take on aspects of “Heimat,” be it the physical or mental aspects.

Xenitia (Greek): In Greek, xenitia is the word we use to encompass places outside Greece, the act of moving abroad and our vast history of self-exile and economic migration. It is a word that brings to mind films, songs, and family histories. It feels painful. It is the Greek expat experience in one word. Source: The Bitter Tea of Xenitia: The beginnings of a digital narrative (Catherine Christaki)

Dor (Romanian): This is one of the words that officially have no translation in other languages. It is similar to the Portuguese “saudade” (which is always included on lists of untranslatable words). It is a strong desire to see someone or something you love, a sort of nostalgia to go back, it’s a pain caused by the love for someone (who is far away). It comes from the Latin “dolere” – to hurt. (Alina Cincan)

Dépaysement (French): “Dépaysement” is the feeling of foreignness one has when they arrive in a setting that’s completely unknown to them. A good example of it would be when a European first lands in Japan – a different language, a different culture, different customs – absolutely no point of reference. Scary? Not necessarily. Tourists often seek that “dépaysement” and therefore choose exotic places to spend their vacation. (Emeline Jamoul)

Infamous people or places

Every language has its special places or famous names that people casually reference in set expressions. Knowing what they mean is the ultimate proof of how well you have learned a language:

Wie bei Hempels unter dem Sofa (German): lit. like under the Hempel family’s couch. This is a hopelessly messy place, a place where dust bunnies, empty bottles and leftover food meet up and party. Often said with a tone of exasperation – think parents of a teenager entering the teenager’s lair: “Hier sieht es ja aus wie bei Hempels unterm Sofa!”

In den Karpaten, in der Walachei, in der Pampa, in Buxtehude (German): lit. in the Carpathian mountains, in Wallachia, in the Pampas, in the German city Buxtehude. Saying something is located in the Carpathian mountains is the German way of saying that is in the middle of nowhere. Poor population of Buxtehude – their city stands as an example of a remote place. Getting there usually involves a long, arduous trip: “Bis hinter Buxtehude muss ich fahren,” said in an annoyed tone of voice (I am headed past Buxtehude, i.e. it takes ages to get there). Quite a few Germans are surprised when they realize Buxtehude is an actual city and not just a made-up place.

“A o întoarce ca la Ploiești” (Romanian): lit. to make a U-turn like they do in Ploiești. – to suddenly and unexpectedly change one’s mind, attitude or behaviour. I have chosen this particular one as Ploiești is actually my native city and it also has an interesting etymology: in the late 1800s, while building the railway lines, not all of them were built at the same time, therefore trains travelling from Bucharest stopped at Ploiești, put on a different track, the engine uncoupled from the first car and coupled to the last one, so people had the impression they were going back to where they came from. (Alina Cincan)

Berlusconismo (Italian): Political neologism meaning the actions and policies of Berlusconi and his party/people. It’s very much used in Italy, you can find it in different contexts: formal, colloquial, journalism, political language, education, etc. The word itself cannot be translated with an equivalent English word. You can use it as a loan or try to explain what does it mean. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Policies_of_Silvio_Berlusconi (Sara Colombo)

Qualunquista (Italian): lit: any-ist. (derogatory) A person whose opinions are heavily biased by an overall distrust in institutions and political parties, and by a general lack of interest/care for the political aspects/implications of living within a society. The term originated in Italian at the end of WWII, where a new political movement called Fronte dell’Uomo Qualunque (lit: Common Man’s Front) hit the scene. The Front was an anti-party movement, which envisioned an “administration-oriented government” with fewer interferences and power in the societal aspects of the country. Even though the “movimento qualunquista” was disbanded well before its 5th birthday, the term was soon adopted by its disparagers to define an overall attitude of non-commitment to politics and civic issues. A possible English translation to describe such an attitude would be “politically uncommitted”; still, such a definition loses most of the nuances conveyed by the Italian term, which result from the historical heritage of the word itself. (Alessandra Martelli)

That certain je ne sais quoi

All cultures have these little quirks that define them. An essence that is almost impossible to describe. Concepts that are unique. Here a few expressions to give you a hint of the little differences between cultures.

Flâner (French): The first one, “Flâner” is a verb used to describe a person taking a stroll aimlessly, without any other particular objective in mind than to enjoy the scenery around them. You would of course think of the verb “to wander”, and I guess this is about the most accurate English translation. However, you would lose all the connotation of the French verb, as “flâner” is strongly associated with Paris and its poetry scene thanks to Baudelaire and his peers, and their use of the “flâneur”. (Emeline Jamoul)

Bêtise (French): The 1st one that comes to my mind is “bêtise”, which would be a mistake or a blunder, I guess, but it does not really translate. It’s the French word which goes with “ooops” 😉 Like you’re painting you’re nails and you’re slipping so your finger is as red as your nail => that’s a “bêtise”. When a child trashes your beautiful plants because they need some attention, they do a “bêtise”. When they go from door to door ringing the bell when everyone is sleeping, they do a “bêtise” too. If your accidentally burn your leather couch while using the iron, that’s a “bêtise” too. (Cécile Joffrin)

Esprit d’escalier (French): Sometimes translated literally in English as “staircase wit“. It means generally only thinking about a witty response right after the moment when it would have been so appropriate. Eg: someone is provoking you or uttering something a bit shocking, and you remain dumbfounded. Immediately after the person has left, you think of what would have been the perfect response. The English Wikipedia page uses the French term as entry, and the origin seems correct (Diderot): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L’esprit_de_l’escalier (Nelia Fahloun)

Przyprawić komuś gębę (Polish): lit. to make someone wear a mug. Polish has many phrases without direct translation into English. These would typically refer to our history, culture, food or slang words. My favourite examples come from the Polish literature, especially from the books by Gombrowicz. He came up with many new words and expressions that have become widely used in the Polish language and found their place in Polish dictionaries. One such expression would be “przyprawić komuś gębę”. Literally it means “to make someone wear a mug”. This idiom describes a situation when someone takes on a social mask or is forced to wear one. It refers to social relations and describes all kinds of habits, conventions and forms that people tend to use when interacting with others. (Dorota Pawlak)

Attaccare una pezza (Italian): lit: patch stitching. To force a (known or previously unknown) person to listen to a never-ending soliloquy about your misfortunes. This idiom is a specifying variant of the more universal “attaccare bottone” (lit: buttonhole, in its figurative meaning.), which is the act of starting a random, long, and boring conversation with someone you don’t really know well. Such a variant is used in several if not all regions of Italy, with slight differences in the extent of its meaning. The variant is unknown probably comes from the habit of revamping worn-out clothes with patches to extend their life … with only the “minor” drawback of making said clothes look even more shabby and miserable. Approximation in English: “forcing someone into a depressing one-way conversation”. (Alessandra Martelli)

Boh (Italian): Idiom, said when asked about something but you don’t know the answer.

For instance: “Pensi che Else verrà alla fest stasera?” “Boh!”

Translation: “Do you think Else will come to the party tonight?” “Boh!”

Meaning: I have no idea. The expression is pretty common within all social groups and also used in media (mainly radio and TV), but it has humble and low origins and you would not use it in formal/professional contexts, unless your relation with the speaker is close. It’s not a swear word or a profanity, I’d say an idiomatic expression often associated with a shoulder movement (up and down) typical of the Italian language. ( (Sara Colombo)

Anstandsstück (German): lit. decency piece/bite. This is the last piece of cake, the last cookie or the last piece of chocolate that no one takes at social gatherings in Germany. Instead, the plate or platter will be carried back to the kitchen with that “Anstandsstück” still on it. Taking it would be greedy and would also imply that your host did not offer you enough to eat. If you really want to eat that “Anstandsstück,” you’d better make sure no one catches you.

Verdauungsschläfchen (German): lit. digestive nap. What Germans do after a big heavy German meal. First, you down a shot of “Verdauungsschnaps” and then you go have a snooze to help your belly cope with all the “Eisbein” and “Sauerkraut” you ate. Older relatives are known to head off for a nap after big lunches at family gatherings. They rejoin the group just in time for the time-honored tradition of “Kaffee und Kuchen” (coffee and cake) in the afternoon.

Sobremesa (Spanish): lit. across the table. This word refers to the time we spend talking to the people we have eaten with after having lunch or dinner. It’s a tradition in Spain to get together with your family on Sunday and to have a long “sobremesa.” (Gala Gil Amat)

Старый Новый год (Russian): lit. Old New Year. The holiday originated from the difference in calendars. Russia used to live according to the Julian calendar longer than the other countries. In fact, the Gregorian calendar was adopted here only a little less than 100 years ago, in 1918. But the Orthodox Church refused to change the calendar of the Church holidays, so the Russian people ended up with two New Years (one according to the Julian calendar, and the other according to the Gregorian calendar). And the New year that is celebrated according to the old, Julian calendar, is called the Old New Year. (Olga Arakelyan)

Meraki (Greek): This is a word that modern Greeks often use to describe doing something with soul, creativity, or love — when you put “something of yourself” into what you’re doing, whatever it may be. Source: Translating the Untranslatable (Catherine Cristaki)

Kefi (Greek): The spirit of joy, passion, enthusiasm, high spirits. A Greek concept of ruthless joyful energy, not only untranslatable, but unexplainable. Not to be confused with mere crockery-smashing. (Catherine Cristaki)

Weise Worte zum Schluss

The true art of translation and language mastery lies in recognizing that language is a form of expression for culture and history. Linguistic forms never exist in isolation, they are tied to a language’s and the individual speaker’s culture and background. Olga Arakelyan used the words “cultural realities” to describe this.

All of the examples above are living proof that a dictionary does not a translator make. In fact, even seemingly very closely related languages struggle to find words to explain concepts foreign to them. Just think of the different variants of English. Lynne Murphy has an entire blog dedicated to the differences between American and British English. Have a look at her summary post for her Untranslatables Month that she stages every October.

The following translators were kind enough to share their thoughts and insights about expressions in their native languages. I am so sorry that I wasn’t able to use all of your suggestions! Olga Arakelyan shared this fantastic Russian expression that refers to subject matter experts: Собаку съел, lit. I ate the dog. Having eaten the dog means knowing what you are talking about really well. Clearly, all of you have eaten the dog of translation.

- Catherine Christaki

- Emeline Jamoul

- Sara Colombo

- Alessandra Martelli

- Alina Cincan

- Karin Krikkink

- Cécile Joffrin

- Nelia Fahloun

- Dorota Pawlak

- Gala Gil Amat

- Olga Arakelyan

I sooo loved this post, Else! So many languages, so many cultures, yet you managed to seamlessly put them together and create this fantastic post. I don’t have enough words to praise what you’ve done here. You can imagine how much I enjoyed reading about other cultures. Thank you!!! And thank you for inviting me to take part.

I’ll be publishing my post for DMB later on today and I hope you’ll like it.

Hi Alina,

I may have lucked out because your suggestions seemed to easily sort themselves into these categories. But I’m glad you like the post 🙂

Thank you for this lovely language journey, Else, and for having me on board.

By the way, in Italian there are 2 different ways to name the Anstandsstück: boccone della creanza (decency bite) or … boccone della vergogna (shame bite) 🙂

Cheers, Alessandra

What a perfect way of saying it – shame bite, indeed!

Lovely post about languages. And you may add also all the subtleties in Spanish in Latin America! where every country uses different idioms to refer to similar things, etc. (see this funny post I found online http://bit.ly/1pW1U4Z). You gotta love language. Happy blogging!

Thanks for your comment.

And I agree, this post is just a tiny slice of all that could be written about language and idioms. We’re not done writing yet 🙂

Best,

Else

[…] good for the translation industry? How cultural insights inform the marcom translation process How culture can sometimes be distilled into a single word 10 Unusual Nature Words We Should Use More Often Can you afford not to attend a translation […]

[…] For the Day of Multilingual Blogging 2014, I take a brief cross-linguistic look at how culture finds its way into language in idiomatic expressions. […]